History

Nearly 140 years ago, The University of Texas at Austin opened with one building, eight professors, and 221 students. Today, UT ranks among the top 40 universities in the world. It is both a community — more than 51,000 students in 18 colleges and schools, their teachers, researchers and staff — and a nation, Longhorn Nation, with a global network of nearly half a million alumni.

The story of that transformation can be summed up in six turning points that made us who we are...

1883

First-Class by Law

In September 1883, The University of Texas was officially opened in a ceremony inside an incomplete building on a grassy hill where the Tower now stands. Classes that semester were held in the temporary Capitol, a three-story building on Congress Avenue housing state government while the current Capitol was under construction. The following January, students reported to the campus and its one building, a ghost of history now known as Old Main.

But the story of UT starts seven years earlier. It began as an idea, one enshrined in the new law of a frontier state:

“The legislature shall as soon as practicable establish, organize and provide for the maintenance, support and direction of a University of the first class, to be located by a vote of the people of this State, and styled, ‘The University of Texas,’ for the promotion of literature, and the arts and sciences...”

—Texas Constitution, 1876, Article 7, Section 10

Giving further shape to this constitutional mandate, by 1905 the university had adopted a motto — the Latin words “Disciplina, Praesidium, Civitatis.” These were meant to capture a famous sentiment of Texian president Mirabeau B. Lamar: “A cultivated mind is the guardian genius of democracy.”

Tying education to the fortunes of our democracy was the premise of the university from the earliest years. Even the Texas Declaration of Independence in 1836 claimed “...it is an axiom in political science that, unless a People are educated and enlightened, it is idle to expect the continuance of civil liberty, or the capacity for self-government.”

This spirit of public service and leadership can be seen in the biographies of alumni like Sam Rayburn, the longest-serving speaker of the House in U.S. history, and numerous governors and cabinet officials. It is seen in the establishment of the LBJ School of Public Affairs, the Strauss Center for International Law, the Clements Center for National Security, and three ROTC programs.

FROM TOP-LEFT: The UT Main Building and Tower under construction in 1936. The Constitution of the State of Texas, established 1876. The seal of the university carved in limestone. Round table discussion at the LBJ School with leaders from Strauss Center & Clements Center on the Intelligence Project.

1923

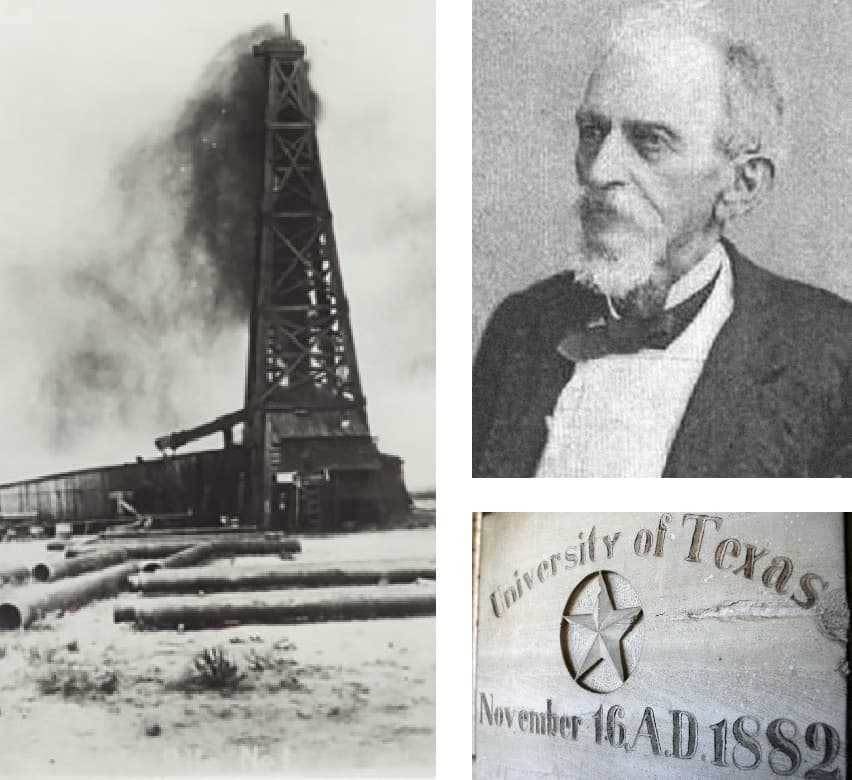

UT might have been built on high ideals and aspirations, but ideals don’t pay for professors or for buildings; money does. In 1882, at a ceremony to lay cornerstone for the university, Ashbel Smith, first chairman of the Board of Regents, said, “Smite the rocks with the rod of knowledge, and fountains of unstinted wealth will gush forth.”

Those rocks were smitten May 28, 1923, when an oil rig named Santa Rita No. 1 “came in” on West Texas land the state had set aside to help fund education, spraying oil over a 250-yard area around the well. A new day had dawned for the university.

Because the fund treated oil profits as principal rather than income, the proceeds from Santa Rita and other wells were reinvested instead of being spent, and by 1925 the Permanent University Fund was growing by more than $2,000 a day. It is no coincidence that during the 1920s and 1930s, 23 buildings went up to create the core of the campus, including UT’s most famous, the Tower.

FROM TOP-LEFT: Santa Rita No. 1 comes in. UT’s first regent chair Ashbel Smith. The cornerstone he dedicated in 1882 is still on view outside UT’s Main Building. UT’s Main Building and Tower under construction in the mid-1930s.

1929

The Research University

UT’s earliest faculty leaders had gambled that a move to Texas, then little more than a wilderness, would be good. By the early-to-mid 20th century, the campus was roamed by intellectual giants like historian Walter Webb, folklorists J. Frank Dobie and Americo Paredes, and Nobel laureate biologist Hermann Muller.

In 1929, the Association of American Universities confirmed that UT was indeed a university of the first class when the AAU invited UT into membership. In Texas, only three universities are AAU members, and UT was the first by more than 50 years.

In 1929, the Association of American Universities confirmed that UT was indeed a university of the first class when the AAU invited UT into membership. In Texas, only three universities are AAU members, and UT was the first by more than 50 years.

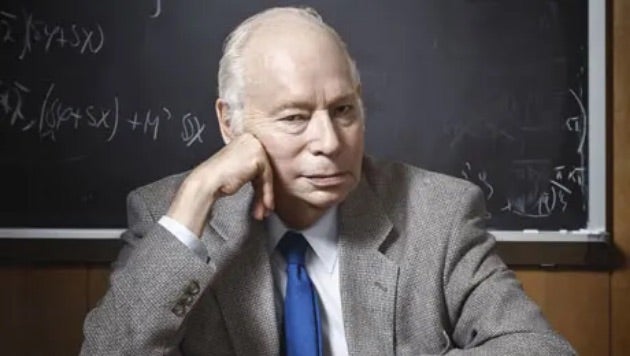

Since then, Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, Maya scholar Linda Schele, and Nobel laureates physicist Steven Weinberg and chemist Ilya Prigogine have further burnished the UT faculty’s global reputation.

Today, UT receives about $800 million a year for research, much of it from federal sources, led by the Department of Defense. UT does “big science.” It has built some of the world’s fastest computers and is a charter member of a consortium building the world’s largest telescope.

FROM TOP-LEFT: Historian Walter Webb, folklorists J. Frank Dobie and Americo Paredes, and Nobel laureate biologist Hermann Muller. Congresswoman Barbara Jordan and Maya scholar Linda Schele. Nobel laureates physicist Steven Weinberg and chemist Ilya Prigogine. One of the world’s fastest supercomputers at UT’s Texas Advanced Computing Center.

1950

A Wider Embrace

In 1950, no flagship university in the former Confederacy admitted black students. That year, the lawsuit of a postman who wanted to earn a law degree at Texas worked its way to the Supreme Court. UT fought integration, but Heman Sweatt prevailed and became the university’s first black student. Sweatt v. Painter became the critical precedent to the Brown case, which finally ended the fallacy of “separate but equal” and began in earnest the slow process of integration.

Twice in the years since Sweatt, UT has gone to bat for the right of universities to affirmatively consider race in admissions. In both the Hopwood case in the 1990s and the Fisher case in the 2010s, the university argued that racial diversity benefited all students, and the Supreme Court agreed.

Because of this history of segregation, UT understands the profound benefits of creating an inclusive environment in which students can learn from one another. The educational benefits of learning on a diverse campus prepare all students to succeed in an increasingly diverse state and interconnected society.

FROM TOP-LEFT: Heman Sweatt registering for courses at the UT Law School in 1950 (Courtesy UT Dolph Briscoe Center for American History). President Gregory L. Fenves comments on the case of Fisher v. The University of Texas at Austin at the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015. Members of the Class of 2019.

1963

The Age of Titans

The year 1963 marked the first time two very different men who made a gigantic impact on the university’s modern character both were in power: Harry Ransom and Frank Erwin.

Harry Ransom came to UT in 1935 to teach English, rose through the ranks, and in 1960 was appointed president, then chancellor of the UT System.

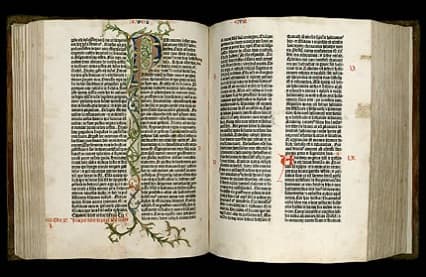

The erudite Ransom had an audacious vision for what the university should be academically, including being a center for globally important cultural holdings like the Gutenberg Bible now housed in the humanities research center that bears his name.

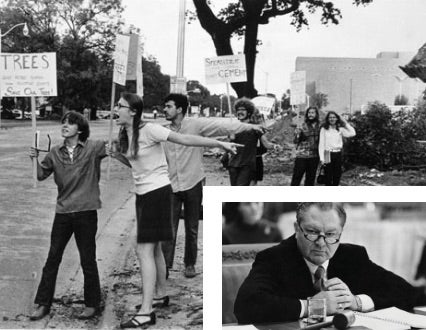

From the time Frank Erwin was named a regent in 1963 until his death in 1983, UT essentially became the university we see today.

Its student population rose from 22,000 to 41,500. Its legislative appropriations rose from $16 million to $100 million, and the campus completed 55 major building projects. Erwin accomplished this transformation through ceaseless work but also powerful connections to the Governor’s Mansion and the White House.

Erwin was viewed by some as heavy handed and remains a polarizing figure to this day, but his influence on the university might never been matched.

The heady 1960s also established UT’s place in the pantheon of collegiate sports, when Coach Darrell Royal led the Longhorns to three national football championships in 1963, 1969 and 1970. They would go on to win another in the 2005 season.

FROM TOP-LEFT: President Harry Ransom. Chairman Frank Erwin. One of 20 surviving copies of the first book printed using moveable type, the Gutenberg Bible was made in the 1450s and acquired by UT in 1978. Students protest the cutting down of trees along Waller Creek in 1969. Coach Darrell Royal (Courtesy UT Press).

2012

A Medical School Comes to the Flagship

By 2012, Austin had become the 11th largest city in America — larger than San Francisco, Boston or Seattle. And it was the largest by far not to have a medical school and teaching hospital. Community leaders, led by state senator Kirk Watson, wanted a medical school to improve health locally. University leaders wanted a medical school for all the good synergies it would create.

When citizens of Travis County voted for a tax to support a school and teaching hospital, Michael and Susan Dell stepped forward with a gift of $50 million, and the Dell Medical School at UT was born, welcoming its first class of future doctors in 2016.

Dell Med is setting itself apart with the audacious goal of changing health care itself and is already a game-changing asset to Central Texas and the university.

Did the people who lived the history of these six years know they would shape the character of the institution? More importantly, what will be the next year that will change Texas?

FROM TOP-LEFT: Downtown Austin as seen from the Tower Observation Deck. Dell Medical School Health Learning Building. Dell Med students. Dell Medical School Health Discovery Building (courtesy Dell Medical School).